Cores to Code: Shaping the Next Generation of Geoscientists

August 6, 2025

Written by Noa Schwartz – CRESCENT Science Communication Intern; University of Oregon Student [2026]

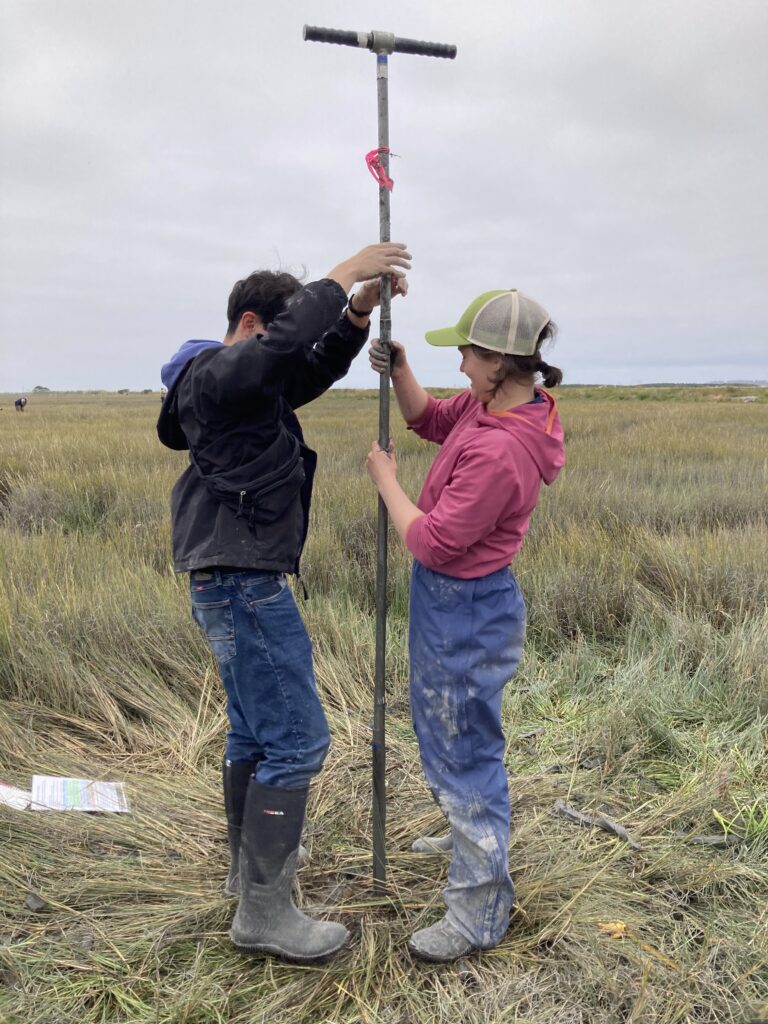

Deep in the coastal marshes of Humboldt Bay near Arcata, California, Sierra Joshua—fresh off her sophomore year at Santa Ana College—drives a drill core into the muck, pulling up a dense column of ancient sediment. Buried in the muck were millions of microscopic organisms—just one of the many things Joshua would learn to identify through CRESCENT’s Cores to Code summer program. She, along with nine other students from around the country, were selected to explore Cascadia’s elusive earthquake and tsunami history. The competition for the program was fierce. Of 172 applications, only ten were admitted. Students were fully supported – each student received a stipend, as well as compensation for food, travel, housing, and equipment.

Their participation comes at a critical time: the earthquake geology workforce is depleted, limiting data collection and slowing progress in our understanding of the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Cores to Code addresses this gap by training the next generation of paleoseismologists through immersive, hands-on experiences. Students engage in the full scientific process—collecting, analyzing, and communicating data—while working alongside leading experts in field, lab and modeling-based earthquake research. By bridging these disciplines, the program empowers undergraduates to test and refine theoretical approaches using real paleoseismic data, advancing both their skills and the broader field of earthquake science.

The program began almost 300 miles from their field site. For two days, students drove from Eugene, Oregon, to Cal Poly Humboldt in Northern California where they would stay for the next 3 weeks. Along the way, they were introduced to the local geology and tectonics of the Pacific Northwest. For Joshua, it was one of the trip’s highlights. As a first-time field researcher, seeing her research subject up close with other geologists was thrilling. “It was both interesting and fun to get to know the area the research was based on while seeing the people and all the pretty views,” Joshua said. “I didn’t have much of a chance to do field work and learn about different areas of earth science. I wanted to experience what it could be like in the field, being around other earth scientists since that wasn’t something I ran into often.”

Similarly, Aaron Punzalan, who just finished his junior year at the University of California – Davis, was new to field research. He heard about the program from his advisor, who recommended it as a valuable learning opportunity in an unfamiliar research space. “Being a first-generation [college] student, there is a lot of intimidation behind participating in research,” Punzalan said. “Widely speaking, most first-generation students aren’t really familiar with how research is conducted. I felt nervous and I felt intimidated, but Cores to Code really changed that perspective for me.”

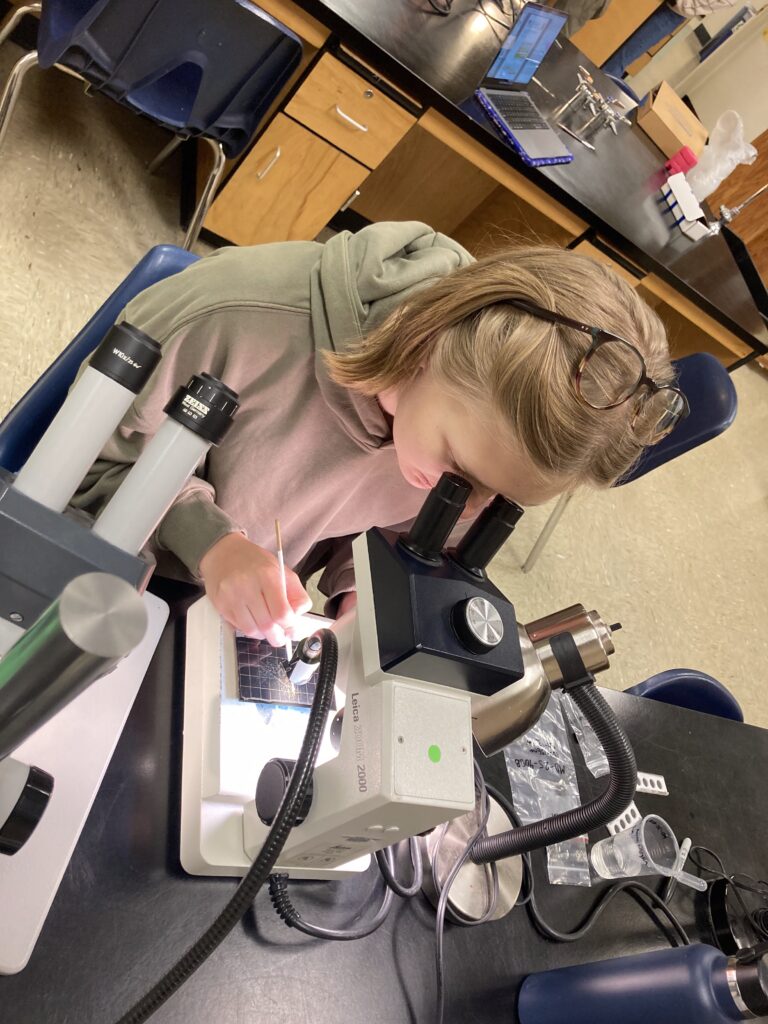

Field work is understandably intimidating, and the marshes were especially harrowing for Punzalan, Joshua, and their classmates. For three days, students sledged through layers of marsh, driving long core drills through centuries of sediment looking for evidence of past earthquakes. Students collected sediment cores and brought them back to the lab for analysis under the microscope. Specifically, they were looking for tiny, single-celled organisms called diatoms and foraminifera. These microorganisms are so specialized that each species occupies only a specific elevational range within the marsh. By identifying species, researchers can infer changes in elevation during previous earthquake and tsunami events and develop models to predict the size of future earthquakes and tsunamis. Joshua, a former oceanography and marine biology student, was surprised to see her worlds collide. Although she had limited experience in traditional geology, she felt at home among her peers. “Before coming, I had no research experience or earth science field experience, so I was worried that I would be somehow underprepared and not fit in because I lack a lot of earth science knowledge compared to others,” Joshua said. “But everything in the program was at a smooth pace, and I understood everything, and I was able to really connect with the other students, making this experience amazing.”

After working in the field, it was time to turn the ‘Cores’ to ‘Code’ and learn how geophysicists use field and laboratory observations to build geophysical models – bridging the gap between theoretical modeling and empirical observations. Students were introduced to Python coding to explore geophysical questions such as: How can we simulate possible future earthquakes on the Cascadia Subduction Zone and compare them to what the Earth tells us happened in the past? Students looked at different earthquake rupture models for Cascadia and tried to find the best match with the geologic evidence.

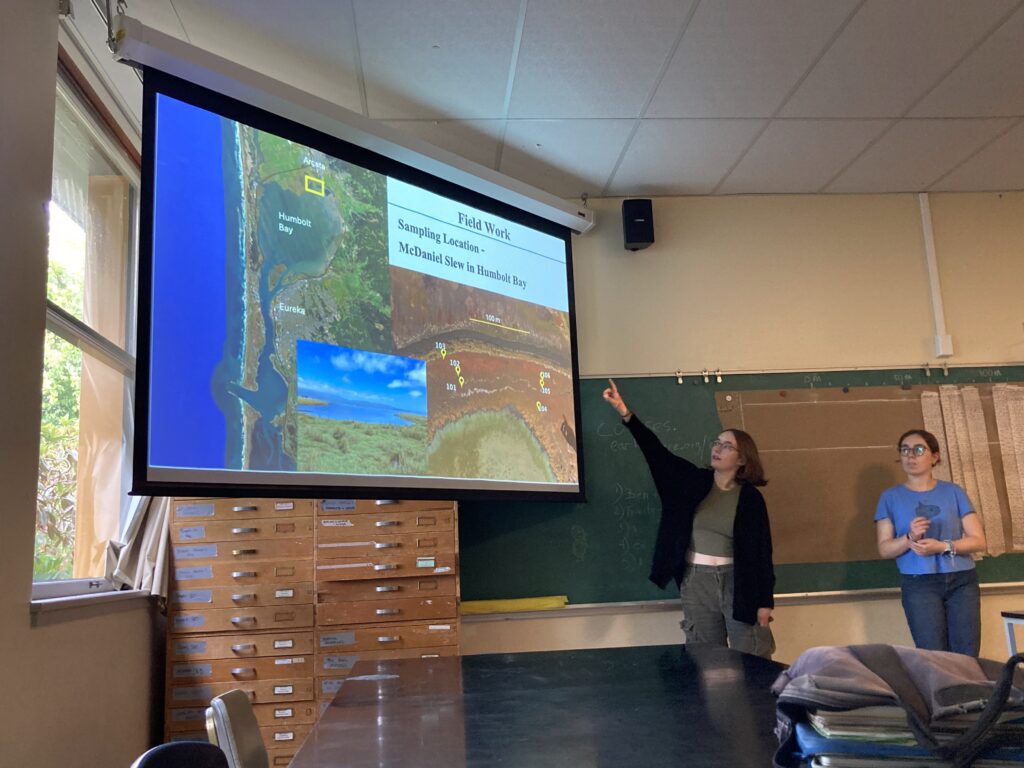

Students ended the program with a final presentation summarizing what they learned from the field, lab, and computational exercises. Each student group had a different target audience: the general public, high school students, emergency managers, scientists, and government policy makers. Students had to put themselves in their audience’s shoes, and tailor their presentations as if they were presenting to their assigned audience. Communication and professional development skills were a top priority for the program, particularly in the context of hazard preparedness. In addition, there was a Meet-n-Greet with local emergency preparedness managers. This was a great opportunity for students to learn about their roles, ask questions, and network.

Collecting data and shipping it off to a lab is one thing—meeting the people whose lives it could change is something else entirely. For Punzalan, it cemented his interest in pursuing a career as a geological engineer. “I really like the applicability behind the research that we were doing,” Punzalan said. “It made me feel like I was making a difference with these tsunami inundation maps. The way that we use the diatoms and foraminifera to inform emergency managers on where or how far these tsunamis are affecting counties like Humboldt, for example – the applicability behind it confirmed that route for me.”

Punzalan hopes to continue working with people like those he met at the California Geological Survey as the next generation of geoscientists takes their places. Cores to Code has given him the confidence to continue to pursue his passion. Joshua is grateful to have had the opportunity to stretch her boundaries both personally and professionally. She intends to continue to challenge herself at her new school, University of California, Santa Barbara, where she will start as a junior this fall. “I think that my confidence has grown and that I have learned to want more in life,” Joshua said. “Before the program, I was worried about stepping out of my comfort zone and trying something new, whether that was trying field research or meeting new people. I realized that that is what life is about, so why not branch out of your comfort zone?”